On Friday, July 31, 1998, a female harlequin duck was spotted on the McLeod River just outside the eastern border of Jasper National Park at 2:10 p.m. in the afternoon. By Sunday morning at 8 a.m., the same bird (identified by its leg band) was observed by biologist Fred Cooke resting on the shore of Boundary Bay, near White Rock, B.C.

“Isn’t that crazy?” said Beth MacCallum, a wildlife biologist with Bighorn Wildlife Technologies who monitors the McLeod River harlequins. In less than two days, this medium-sized duck weighing no more than 1.5 pounds had flown roughly 600 kilometres. Cooke noted that she seemed “sleepy,” and had likely just arrived.

MacCallum studies the McLeod River nesting site to understand if the nearby Cheviot Mine is having an impact on the duck’s population. However, she has long been interested in understanding more about their migration, and for many years has kept in touch with biologists on the west coast (like Cooke) to get observational data about the duck’s flight times.

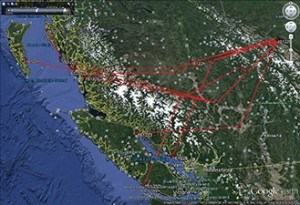

Her chance to learn exactly when and where McLeod River harlequins were flying came last year when she joined an international study led by Sean Boyd, a scientist with Environment Canada based out of Delta, B.C. The team equipped male harlequin ducks from six nesting sites in North America–including the McLeod River–with satellite trackers. This allowed the scientists to follow their movements from their nesting grounds to the coast last summer, and back again this year in late April or May. The results from the first half of the journey yielded some surprises.

“We suspected that they fly straight to the coast, but had very little information to back that up,” says MacCallum. Data obtained from the satellite trackers showed that her birds did just that–flew to their coastal wintering and molting grounds in under two days. However, a couple birds had something else in mind. Two of them touched down in central B.C.–one for ten days, the other for 17 days. This behaviour was previously unheard of. “There seems to be two strategies to get to the coast,” said MacCallum.

MacCallum was also surprised that none of the birds from the McLeod nesting site went to the same place for the winter. “My birds were found from Sechelt, Sunshine Coast, all the way up the coast to Alaska.” She said they may be splitting up to spread out their risk.

Migrating harlequins are vulnerable to big storms, collisions with buildings, and disorientation from light pollution, among other threats. At their wintering grounds, they may be affected by oil spills, human development and activities that decrease habitat, and hunting (in part because females and immatures can resemble other species which may be legally hunted). By spreading out along the coast, there is less chance that an entire nesting population will be lost in a single event.

This study has already yielded information that may be useful in protecting the birds, which are federally listed as a species of special concern under Canada’s Species at Risk Act. For example, the satellite tracking data suggests that Queen Charlotte Sound, Vancouver Island, and the Salish Sea are important molting and wintering areas.

This spring, MacCallum and the team will get the other half of the bird’s migration story. Soon they’ll return to their nesting areas, perhaps with more secrets to share.

Niki Wilson | Special to the 51����

MacCallum’s part of the study was funded by Teck Resources Ltd and West Fraser through the Forest Resource Improvement Association of Alberta (FRIAA).